Xi Talks AGI + The UK’s S&T Policy Renaissance

Can the Politburo solve the alignment problem?

Irene—Is Xi a Doomer?

According to Xinhua, the CCP Politburo chaired by Xi met on April 28 to talk about “the current economic situation and economic work.” On technology, the readout said:

The conference emphasized the need to accelerate the construction of a modern industrial system supported by the real economy. This requires both going against the tide to achieve breakthroughs in areas of weakness and capitalizing on favorable trends to grow and strengthen areas of advantage. We must solidify the foundation of self-reliance in science and technology and cultivate new growth momentum. It is essential to consolidate and expand the advantages of new energy vehicle development, and accelerate the construction of charging stations, energy storage facilities, and the renovation of supporting power grids. Attention must be given to the development of general artificial intelligence, fostering an innovative ecosystem, and prioritizing risk prevention.

It appears to be the first time the phrase “AGI” made it into a statement attributed to Xi himself. It’s not the first time “AGI” has entered official parlance in China, but its use by Xi and the Politburo will likely lead to further proliferation within Chinese discourse.

It’s worth noting that while in the West AGI is more a term for sci-fi than politicians, Chinese officials have apparently embraced it wholesale. Back in 2019, the Procuratorate Daily (the newspaper published by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate) published an op-ed discussing the challenge of criminal attribution for “AGI robots.” Beijing’s municipal government began funding an “AGI Innovation Park” in 2021. Last year, Hangzhou’s Binjiang District published a puff piece about Qian Xiaoyi, the founder of AI startup Galaxy Eye (and distant relative of Qian Xuesen, the father of Chinese rocketry who migrated to China only after McCarthy-era persecution) who “harbors a beautiful dream of changing the world with AGI.”

What exactly needs to happen before China can declare that it has achieved AGI? And what does the Politburo mean by “prioritizing risk prevention”? Only time will tell…

The UK’s S&T Policy Renaissance?

Guest piece by Tom Westgarth, Senior Analyst at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

Is UK science and technology policy back on the menu? Four years ago, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson set out an ambition to restore the country’s place as a science superpower. In a political arena thrown up in the air by Covid and Brexit, this was music to the ears for many: to succeed in the twenty-first century, science and tech needs to be central to our national purpose.

Since then, the “banter era” of British politics that had begun following the Brexit vote has resurrected its head. In what feels like a distant but permanently etched memory, Prime Minister Liz Truss lasted just forty-nine days last October, as her efforts to stimulate growth by unfunded tax cuts decimated her support. In her place stepped the “safe pair of hands,” Rishi Sunak, who restated the ambition of becoming a science superpower by 2030. Where this government has become defined by many unsubstantiated slogans, the science superpower agenda has actually seen some good wins.

The most symbolic of these has been the creation of a new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology with a first Cabinet-level role for science and tech. Previously, matters relating to science and technology were awkwardly lodged between the old Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. As a result, no department took true responsibility. And having a Secretary of State who covered tennis, cinema, and algorithms? This was probably not the best division of labour in the history of government.

A number of other striking ideas have surfaced too. £50 million has been signposted for Focused Research Organisations (FROs): small teams which pursue specific, quantifiable technical milestones rather than doing blue-sky research. £900 million has been put toward building a supercomputer and a National AI Research Resource. An extra £100 million has been earmarked for the foundation model taskforce, which will aim to integrate the latest AI models in public services, developing UK companies via the procurement process along the way.

An aggressive STEM talent agenda has arguably found a home in the UK government. A new AI talent programme has been touted, following last year’s High Potential Individual Visa, which has drawn talent to UK shores by allowing graduates from top global universities to come to Britain without a job offer. Elsewhere, the UK’s medicine and medical device regulator is set to enable pharmaceutical reciprocity from other regulatory authorities. Goodnight, precautionary principle — hello, safe and efficient regulatory regimes.

But the jewel in the crown of UK science policy is the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA). Based on the US ARPA model, ARIA funds high-risk, high-reward research around potentially game-changing technologies. In a landscape where government tends to be risk-averse, and thinks about funding in short-term political timelines, ARIA could be part of the antidote that UK science and technology policy needs.

This shift in the mindset of the UK government is made all the more notable by its leadership: two young entrepreneurs. The founder and former CEO of Activate, the American Ilan Gur, and the founder and CEO of Entrepreneur First, Matt Clifford, have been brought into Whitehall.

[Ed. I had Ilan Gur on a past ChinaTalk!]

How to Do R&D Right

Last night Endless Frontier aka the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act passed the Senate by a 68-32 margin. As covered on previous ChinaTalk editions, a core piece of this bill authorization to pour billions into Amerca’s R&D establishment. In the runup to the bill, over the past two weeks on the ChinaTalk Podcast I had on two PhDs who are working on fi…

Many of these new ideas, and the overall break with conventional thinking, are downstream of the “misfits and weirdos” era of the Boris Johnson administration. The former PM gave his chief adviser Dominic Cummings free rein over much of Britain’s science and technology policy until Cummings’s departure in 2021. Perhaps better renowned for being the architect of the UK’s exit from the European Union, his stated priorities were actually twofold: “Get Brexit Done. Then ARPA.”

Other officials such as Sir Patrick Vallance and Dame Kate Bingham, who led the Covid vaccine taskforce, were also critical in raising the salience of science and technology in government. But despite this success, there is still a broken model at the heart of UK science and tech policy.

The UK now finds itself in a tricky reality: as a smaller nation, it risks being squeezed by giants. Unable to compete with the scale of the technological superpowers of the US, China, or even with the collective weight of Europe, the country needs to find its place in this new world. Semiconductors, batteries, and AI are increasingly the critical strategic technologies shaping the modern age and the world we live in. The IRA and CHIPS Act, along with big European subsidies programmes, blow any potential intervention that the UK could do out of the water.

British economic growth is in the gutter. Out of the G20 countries, only Russia is forecast to have worse economic growth this year. Think the UK is a world leader in research? You might want to reconsider. If you exclude DeepMind, Britain is arguably a middle-ranking advanced economy in frontier AI research.

The state can often move at a snails pace. The overly powerful Treasury consistently blocks R&D funding, while an excessive “audit culture” of science spending (and a beleaguered planning system) halts research and the development of critical modern infrastructure.

So, what do we think should be done to end Britain’s place as the stagnation nation? In the Tony Blair Institute (TBI) For Global Change’s recent paper “New National Purpose,” we set out a radical but achievable plan for how Britain can meet the challenge of the modern era.

Three of our favorite recommendations include:

Creating an Office for Science and Technology Policy that sits between the two central nodes of the UK state, Number 10 and the Cabinet Office. This would be modeled on the White House Office for Science and Technology Policy, which would have the status to attract superstar talent, and have the Prime Ministerial authority to unblock key issues.

Developing domestic AI infrastructure for public service delivery. This would also help to provide compute resources to startups and academia.

Incentivizing pensions consolidation and encouraging growth equity by making the pension capital-gains tax exemption applicable only to funds with over £20 billion under management that allocate a minimum percentage of their funds to UK assets; and combining the UK Pension Protection Fund (PPF) and the National Employment Savings Trust (NEST) to create a single investment vehicle that participates in market consolidation.

We don’t want to see any more charts that show “UK going up on bad thing.” We don’t want to see any more stories about us not investing in key capabilities because they are “complex and nuanced.” At this point, these themes are unfortunately part of the furniture of UK public policy. The “banter era” of UK politics needs to end. The age of 21st-Century technology progress needs to begin.

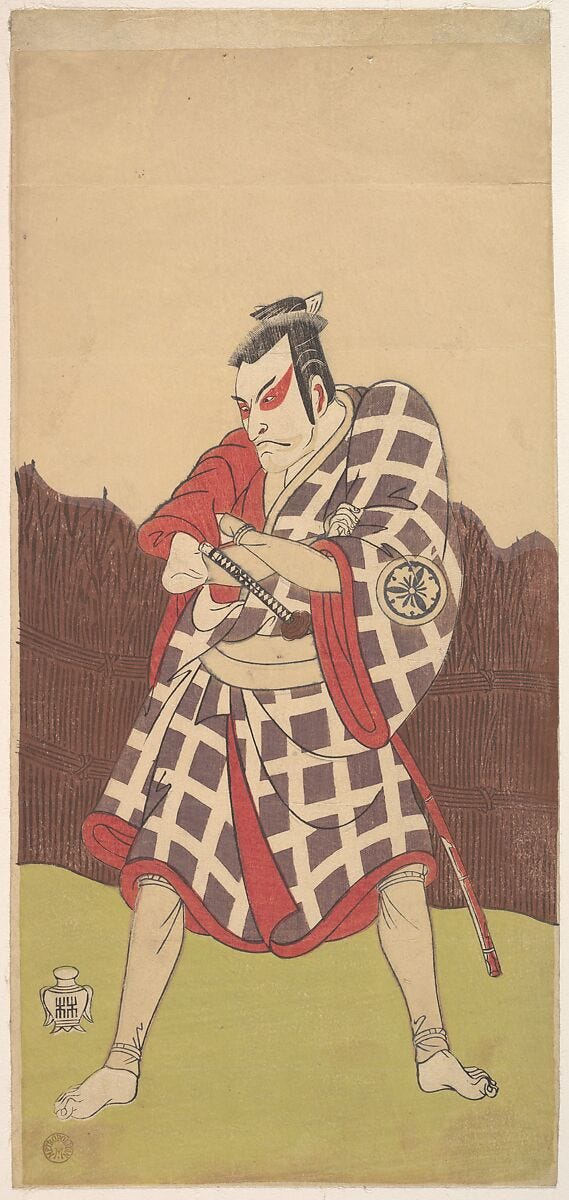

Real art for a change!

Title: The Actor Matsumoto Koshiro 3rd as a Man who Stands with Arms Folded near a Brush Fence

Artist: Katsukawa Shunshō 勝川春章 (Japanese, 1726–1792)

Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

Culture: Japan

Medium: Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

Are the small model, light compute, open source models a threat?

It seems obvious that Paul Scharre, Greg Allen and the Biden administration are right:

Scharre said to Jordan on China Talk: "...compute - access to AI chips - is the key point of leverage over access to AI capabilities..." (https://link.chtbl.com/ChinaTalk); and,

Greg Allen agrees with the Biden chip strategy (https://www.csis.org/analysis/choking-chinas-access-future-ai): "In short, the Biden administration is trying to (1) strangle the Chinese AI industry by choking off access to high-end AI chips; (2) block China from designing AI chips domestically by choking off China’s access to U.S.-made chip design software; (3) block China from manufacturing advanced chips by choking off access to U.S.-built semiconductor manufacturing equipment; and (4) block China from domestically producing semiconductor manufacturing equipment by choking off access to U.S.-built components."

But how should we assess the power of the fast moving advances in small, even locally run, open source models summarized in the leaked Google memo (https://www.semianalysis.com/p/google-we-have-no-moat-and-neither)? Apparently they can be almost as good. Does all this make deploying a practical level of AI (not for autonomous applications but for assisting human performance) more achievable for the Chinese even in the face the chips embargo?

(Sorry....I'm trying Notes for the first time and can't figure out how to put this comment in the best place....)